Two Lousy Letters, a House of Cards, and a System Tested

- Julie O'Connor

- 1 hour ago

- 6 min read

When Two Bank Letters Tested Governance

In 2013, during my own inquiries into what appeared to be a conspiracy to defraud my husband, I encountered two letters said to have been issued by DBS, Singapore’s government-linked bank. Dated 30 July and 11 September respectively, they immediately stood out as problematic.

My unease was instinctive, even before any technical analysis, something about the letters simply did not sit right. Even our lawyer remarked on them as soon as they arrived. Others, since then, have made the same observations. The letters contained typographical errors, missing sender details, questionable signatures, and formatting inconsistencies. They bore little resemblance to any correspondence we had previously received from DBS, a bank we had dealt with for years. These were not minor irregularities, and they would soon play a pivotal role in a transaction with very real financial consequences.

But what followed was never just about the authenticity of two letters. It became a test of governance and oversight, and a measure of whether the Singapore systems designed to protect investors and market integrity could withstand sustained pressure.

The Commercial Context

At the time, DBS was the principal banker to the Singapore subsidiary of Strategic Marine (SM), an Australian-owned shipbuilding group with operations in Australia, Singapore and Vietnam. SM had been through a difficult period, but by the second half of 2013 it was starting to turn around. Operations were improving, and by mid 2014 the group would go on to record more than A$15 million in net profit after tax and pay substantial dividends.

At the same time, DBS had significant exposure to EZRA Holdings, an SGX-listed offshore and marine group whose financial position was deteriorating. The EZRA board had decided to spin off a subsidiary, Triyards, which would be used to acquire Strategic Marine (SM). The acquisition would provide Triyards with a diversified product line, new customers, and a valuable order book, and it may have financially benefited the EZRA and Triyards board member, who at the time held a claim to an undisclosed beneficial interest in a shareholder of SM.

Likened to a John Grisham Novel

But this was not only about two lousy DBS letters.

When a former managing director of a Singapore government-linked company heard about my journey to uncover the truth, and reviewed our evidence, he remarked that it read like a John Grisham novel. But one suspects Grisham might have rejected it as implausible. A company whose fortunes were improving was nonetheless shepherded toward a “necessary” sale to an SGX-listed group itself heading squarely for an iceberg. The acquisition’s value was written down by as much as 97%, just two weeks after a valuation and in the lead up to an acquisition attempt. This dramatic devaluation was attributed to the timely appearance of two remarkably shoddy, but curiously effective, bank letters.

Lousy letters aside, it could not be described as a straightforward, by-the-book acquisition by the SGX-listed group. A so-called “trustee,” described as a close acquaintance of the EZRA and Triyards board member, was appointed to assist. He happened to be the CEO of another SGX-listed company, who was later reported to have been convicted and imprisoned for unrelated white-collar offences. But in our story, he was tasked with the vital role of not actually buying anything but merely giving the impression that he was.

He was to notionally acquire Strategic Marine and a related company, entities over which he held power of attorney. I say “notionally,” because if his genuine intent had been to acquire these entities at a bargain basement price from the outset, he would not have pre-assigned and pre-cancelled his irrevocable options. Unless, of course, he will now claim that his signature was also forged, and that he had no knowledge of the documents on which it appeared. Then, the rabbit hole would only get deeper.

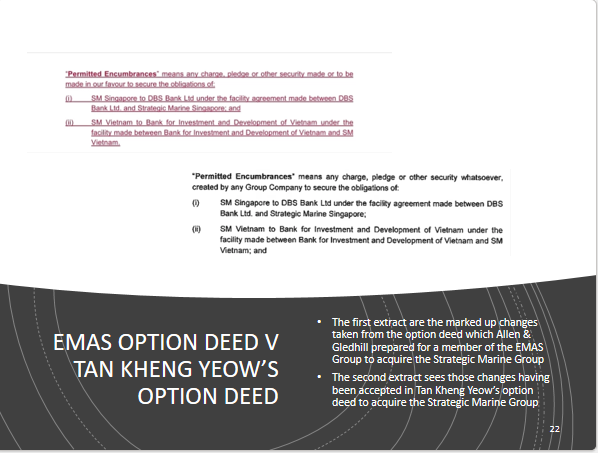

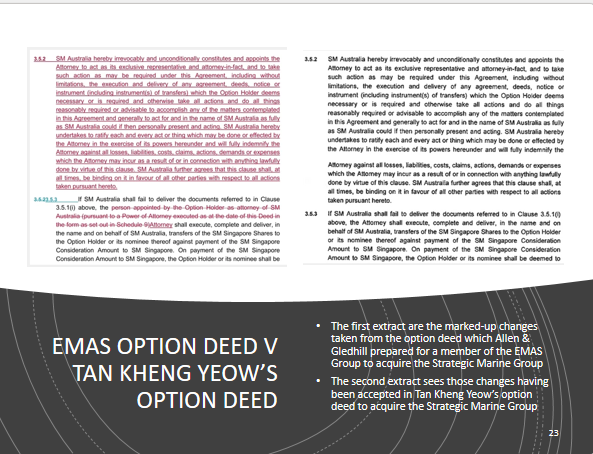

From the documents provided, it does appear that the same Singapore law firm was involved in drafting option deeds for both the purported “trustee” and a member of the EZRA Holdings group to acquire the same entity, Strategic Marine Pty Ltd (later renamed Henderson Marine Base Pty Ltd). Whether both sets of option deeds were genuine, and both parties were clients of the law firm, is a matter best addressed by those concerned.

Planned acquisitions that made strategic sense when considered together were deliberately scheduled to be announced weeks apart, for reasons known only to their architects. I was told that the plan, to be concealed from the market, was designed to inflate the share price of a SGX-listed company, potentially generating substantial profits for those with inside knowledge. Allegations of forged signatures, a conveniently hidden writ, inducements to keep silent, and directors abandoning ship before disaster struck, completed the troubling picture.

Now whether this represents a shining example of Singapore’s corporate governance, or a live experiment in how much distortion a market will tolerate before it blinks, is, of course anyone's guess. Each layer of complexity must have served a purpose, and the opacity of the transaction did not appear to be incidental; but more structural.

The Question of Authentication

Given the use and timing of the DBS letters, it was entirely reasonable for our lawyer to request that DBS confirm whether the two letters were authentic, and whether they served legitimate purposes. It took nearly eight weeks for Group DBS Legal, Compliance and Secretariat to respond, ultimately refusing to authenticate the letters, citing banking secrecy. Meanwhile, during that prolonged delay, the asset transaction quietly went through.

Between 2014 and 2020, DBS conducted four internal investigations, alongside two separate whistleblower submissions. Over that period, the senior staff liaising with me and overseeing the investigations, unfortunately either resigned or were transferred. The two PwC partners in charge of the audit to whom I had also raised concerns similarly moved on.

An independent forensic document examiner stated that the DBS letter lacked credibility, but external legal advisers appointed by DBS later confirmed that the DBS letters in question were indeed authentic. I was advised that I was not permitted to disclose this conclusion, including to those who had conducted the investigations themselves and left. Subsequently, a whistleblower was instructed not to make any reference to the two DBS letters in his submission, and not to inform DBS of that instruction, which was given by a senior DBS staff member.

Against that backdrop, the characterisation by external lawyers appointed by DBS of my actions as malicious is striking. It appears to proceed on the assumption that the surrounding events were routine and unworthy of serious scrutiny, and that the act of questioning governance itself was the aberration.

Why Do Lousy Bank Letters Matter Anyway?

They matter because bank letters/documents carry real weight. They can influence valuations, transactions, investor decisions, and the exercise of legal rights. When such letters are deployed in high-stakes transactions, their authenticity and purpose must be beyond doubt. That principle was underscored in the UK in the Watford FC case, where the club was fined £4 million over the use of a forged bank letter.

As was stated just last week in a case involving the use of a forged document, ironically in an attempt to cheat DBS bank, forgery for the purpose of cheating is punishable in Singapore by up to 10 years’ imprisonment and a fine. Yet the Singapore Police declined to investigate any of my complaints, citing “insufficient evidence”. This is particularly striking given that the evidence was the subject of a financial offer by a member of the EZRA Holdings board to secure silence.

That sequence alone raises uncomfortable questions about consistency and whether evidentiary thresholds shift when powerful or conflicted parties are involved.

I will continue to speak up to ensure these questions are not buried, ignored, or forgotten, because when transparency and compliance fail, it is not just a company or a transaction that suffers; it is the market itself. The cost is borne by every investor and member of the public who relies on those systems to function as intended.

Perhaps the hope is that by the time the fog lifts, the ship has not merely changed hands but has already sailed beyond the reach of those still asking questions! Are we there yet?

Bought, Buried and Ignored - https://www.bankingonthetruth.com/post/bought-buried-and-ignored

Comments